Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Bebés e impuestos

El gobierno estadounidense da un descuento en los impuestos de $1000 por hijo. El pequeño detalle es que si tienes el hijo el 31 de diciembre de 2006, recibes los $1000 correspondientes al año 2006, mientras que si tienes el hijo el 1 de enero del 2007, pierdes el dinero del 2006.

Parece ser que esto tiene un efecto secundario (que cualquier economista podría haber previsto): algunas personas le piden a sus ginecólogos que les adelanten los partos para asegurarse de que cobran el dinero:

Es decir: que en los últimos años, el periodo en el que más niños nacen es entre Navidad y Año Nuevo, lo cual es consistente con la hipótesis de que la gente lo hace motivada por el ahorro de impuestos.

Parece ser que esto tiene un efecto secundario (que cualquier economista podría haber previsto): algunas personas le piden a sus ginecólogos que les adelanten los partos para asegurarse de que cobran el dinero:

Unless you’re a cynic, or an economist, I realize you might have trouble believing that the intricacies of the nation’s tax code would impinge on something as sacred as the birth of a child. But it appears that you would be wrong.

In the last decade, September has lost its unchallenged status as the time for what we will call National Birth Day, the day with more births than any other. Instead, the big day fell between Christmas and New Year’s Day in four of the last seven years — 1997 through 2003 — for which the government has released birth statistics. (The day was in September during the other years; conception still matters.) Based on this year’s calendar, there is a good chance that National Birth Day will take place a week from tomorrow, on Thursday, Dec. 28.

By my calculations, about 5,000 babies, of the 70,000 or so who would otherwise be born during the first week in January, may have their arrival dates accelerated partly for tax reasons.

Es decir: que en los últimos años, el periodo en el que más niños nacen es entre Navidad y Año Nuevo, lo cual es consistente con la hipótesis de que la gente lo hace motivada por el ahorro de impuestos.

Saturday, December 02, 2006

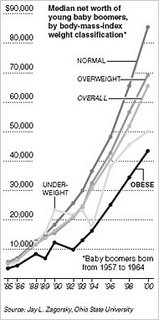

Sobrepeso y nivel económico

Aquí hay un artículo interesante sobre la correlación entre el sobrepeso de los ciudadanos estadounidenses y su nivel de ingresos:

Heavy people do not spend more than normal-size people on food, but their life insurance premiums are two to four times as large. They can expect higher medical expenses, and they tend to make less money and accumulate less wealth in their shortened lifetimes. They can have a harder time being hired, and then a harder time winning plum assignments and promotions.

Es decir, las personas con sobrepeso no solo tienen costes de seguro médico entre 2 y 4 veces más altos que el resto, sino que también ganan menos dinero, ahorran menos dinero durante su vida (que es más corta) y además tienen más problemas para ser contratados y para conseguir promociones en sus empleos.

Otro análisis interesante:

This year, two nutritional scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Rachel N. Close and Dale A. Schoeller, took a unique twist on the calculations to determine what “supersizing” a fast-food meal costs society. Paying 67 cents to supersize an order — 73 percent more calories for 17 percent more money — adds an average of 36 grams of adipose tissue. The future medical costs for that bargain would be $6.64 for an obese man and $3.46 for an obese woman. “The hidden financial costs associated with weight gain from upsizing a value meal may help convince people it is not a bargain,” Mr. Schoeller said.

Es decir, cada vez que se pide una hamburguesa "supersize" en vez una normal en un establecimiento de comida rápida, los gastos médicos esperados se incrementan en $6.64 para un hombre obeso y $3.46 para una mujar obesa.